It was a time of war and uncertainty as the restless teen awoke to face another day on the homefront.

It was a time of war and uncertainty as the restless teen awoke to face another day on the homefront.“Salva, levantate hijo. Se te va hacer tarde," his mother Dolores said as she gently nudged him awake.

As Salvador made his way through the crowded streets of San Antonio, he no doubt contemplated his future.

In the spring of 1944, the streets of the city were buzzing with activity. Newsstands flashed the latest war news and uniformed soldiers paraded Downtown as they prepared to join the fight overseas.

Despite the war, life rolled on. Privileged kids juggled books and malt shakes at nearby Fox Tech or Lanier High Schools. In the barrios of the city, economically-disadvantaged Mexican-American youth followed a long-held family custom summed up in a phrase they heard from the moment they reached early adolescence:

“Pongansen a trabajar” – go get a job.

Many simply couldn’t afford the luxury of a high school education at a time when they were expected to begin contributing to the family finances. Most were resigned to a working life at one of the several livestock yards and meat packing plants that lined Frio City Road on the southern edge of San Antonio.

Salvador’s formal education had long ended and the small pay he managed to bring home every week helped put food on his mother’s table. With the help of his married sisters Consuelo, Adela, Amparo and Hortencia, Salvador and his widowed mother managed to get by.

But the war had become an all-consuming concern for everyone. America was preparing for the invasion of Europe. D-Day was just around the corner. All around, neighborhood boys slightly older than Salvador were lining up at recruiting offices to be screened for eventual combat duty.

Culturally, they barely fit in. Most of the teenagers in the barrio were first or second-generation immigrants from Mexico whose families had settled in a vast area south and west of the Downtown area. It was a nondescript Mexican neighborhood dotted with clapboard homes on gravel and caliche streets with names such as Hazel, South Zarzamora, Buena Vista and Calle Guadalupe.

Already, hundreds of young Mexican-American men who heeded the call to service were away fighting and dying in places like Midway, Italy and North Africa.

But it wasn’t Salvador’s turn just yet. He was only 16 and Uncle Sam had no intention of letting him follow his older brother Luis into the Army. Clearly, he had to bide his time for a while longer before he was old enough to join the war effort.

And so Salvador waited.

Young and full of life, he loved the hustle and bustle of the city. On weekends, he donned his pin striped suit and fedora and hit the social scene at the Municipal Auditorium where the city held dances and ice cream gatherings.

Over time, he became wise to the ways of the street. He marveled at the constant comings and goings of people on Houston and Commerce Streets and enjoyed hearing about the war from soldiers who had just returned from combat. He often bragged about his brother Luis who was soon headed for the war front.

It wasn’t long before Salvador managed to talk his way into a job at the big army air base at Randolph Field on the other side of town. While there, he made it known to his superiors he was anxious to join the fight now – not later.

With the war going full tilt, every able-bodied American male was needed. As Salvador walked up to the base recruitment office, a cigar- chomping Army sergeant barked out questions about his birth date and place of birth.

“June 6, 1927. Helena, Arkansas, sir,” was Salvador’s reply.

Not realizing Salvador hadn’t quite reached his 17th birthday, the sergeant hurriedly pushed him into a line of raw recruits destined for basic training. After tearfully saying goodbye to his mother Dolores, he boarded a train headed for Fort Belvoir, Virginia.

During several weeks of grueling training, Salvador realized how good a soldier he would be. He enjoyed the strict training regimen that included learning how to shoot an M-1 rifle and a machine gun. He was also trained to load ammunition onto tanks and other armored vehicles. His eventual job, he was told, was to be a combat engineer building bridges and doing other construction work.

On weekends, the recruits were taken by bus to nearby Washington, D.C. where they visited the sites and spent time resting and relaxing. All around there was entertainment and opportunities for socializing. There were big band dances and clubs where soldiers could drink and play dominoes and cards all weekend.

Salvador recalls standing next to the stage while the famed Andrews Sisters entertained the troops. Later, during a weekend trip to New York City, he visited the restaurant owned by legendary boxer Joe Lewis.

Not much of a drinker, Salvador often treated himself to nickel hot dogs and Pepsi Cola at the nearest USO club. The best part of his USO visits, he later said, was all the free ice cream he could handle.

Graduation from basic training finally arrived. Private S.V. Ortega posed proudly in his fresh uniform for a photograph that would soon grace his mother's living room back in San Antonio.

After basic training, his unit remained stateside for a few more months while the war in Europe began turning in America’s favor. Throughout the rest of 1944, American forces continued to push across France fighting battle after brutal battle against the Nazi menace. Finally in the spring of 1945, orders arrived for Salvador’s unit to deploy to Europe.

The soldiers boarded a troop ship in New York City harbor for the two-week journey across the Atlantic.

Salvador recalls a piece of advice his older brother Luis offered him before boarding the ship. “Make sure you buy a big bag of lemons before you get on the ship,” wrote Luis.

Halfway across the ocean, soldier after soldier began falling ill - the effects of scurvy – a condition brought on by the lack of vitamin C. But Salvador sat comfortably in his bunk - sucking happily on his lemon slices. As the ship neared its destination, members of Salvador’s unit nervously anticipated their entry into combat. But just as the troop ship pulled into port at La Havre, France, Nazi forces surrendered to the Americans at Ruhr, Germany. At nearly the same time, German troops surrendered to Allied forces in Italy and the

Soviet Army surrounded Berlin.

On April 30, Hitler committed suicide in his underground bunker.

The war was essentially over, but there was much work still to be done. Post-war Germany suffered from a lack of any substantial law enforcement capability.

The job of keeping the peace after the war fell on the U.S. Army Constabulary which was quickly organized under Major Gen. Ernest N. Harmon.

The job of keeping the peace after the war fell on the U.S. Army Constabulary which was quickly organized under Major Gen. Ernest N. Harmon.More than 35,000 American soldiers culled from some of the best units in the Army were assigned to constabulary duty. Their job was multifold but specific:

-Organize and maintain a police presence in post-war Germany

-Hunt down Nazi war criminals

-Assist displaced civilians

Salvador was quickly reassigned to the 11th Constabulary Regiment, 51st Squadron, “A” Troop. The unit was headquartered in Southern Germany near the Austrian border.

Salvador recalls details of his duty:

“After arriving in Passau, Germany, I was assigned to the 51st Constabulary Squadron and there were only about 15 soldiers. We were staying in hotels and we patrolled about 50 miles a day. We were affiliated with the Counter Intelligence Corps Criminal Investigation Division.” The division became known for its successes in tracking down Nazi war criminals.

The region where Salvador’s unit was assigned to patrol was stunningly beautiful. The landscape featured high alpine forests, clear blue lakes and snow-capped mountains.

The 51st Constabulary Squadron focused on secret correspondence between agents in the field and their superiors in the Provost Marshal’s office.

“We would deliver correspondence to (and from) a secret agent somewhere in a village or small town,” Salvador wrote. “We traveled in a jeep with a patrol leader and an interpreter who was also a (German) policeman.”

Salvador’s unit maintained close contact with German civilians throughout their mission. Downtrodden and war-weary men, women and children were struggling to get their lives back in order after the war. Salvador recalls helping provide food and shelter for thousands of displaced civilians.

“The people were hungry and always asking for food. But there were too many of them, especially young kids and young ladies. They would offer to wash our (uniforms) for a few cigarettes and candy,” wrote Salvador.

Salvador talks about having a strong affinity toward the German people. In a photo he sent home, he noted how closely a child he befriended resembled his own nephew back home.

Salvador’s tour of duty in post-war Germany came to an end in early 1947.

The U.S. Army Constabulary continued to serve with distinction in Germany until 1953.

Editor's note: This article was authored by Roy Ortega, oldest son of Salvador V. Ortega. Roy is the Multimedia Editor for the El Paso Times in El Paso, Texas. Salvador was married to Rebecca Ramos Ortega for 53 years before she passed away on January 3, 2003 in San Antonio, Texas. The couple's other children are Etna Rose Ortega of Castroville, Texas, Ruben Ortega, Yolanda Ortega Beltran, Nora Ortega Fenske, and Rebecca Ortega Keller, all of San Antonio, Texas. Salvador passed away on November 1, 2007 in San Antonio, Texas. Roy Ortega may be reached at rortega54@elp.rr.com

The couple's other children are Etna Rose Ortega of Castroville, Texas, Ruben Ortega, Yolanda Ortega Beltran, Nora Ortega Fenske, and Rebecca Ortega Keller, all of San Antonio, Texas. Salvador passed away on November 1, 2007 in San Antonio, Texas. Roy Ortega may be reached at rortega54@elp.rr.com

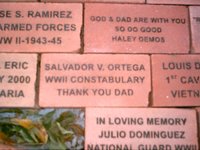

Veterans Walk of Honor Pays Tribute To S.V. Ortega, Winter of 2006

SAN ANTONIO, Texas – In gratitude for his dedicated service during post-World War II Germany, S.V. Ortega was awarded a place of honor on the grounds of the oldest VFW post in Texas.

On behalf of the Ortega family, daughter Etna Ortega secured an ornamental brick bearing S.V. Ortega’s name and military unit which will be permanently displayed in front of the historic Petty House located near Downtown San Antonio.

The house, which was built in 1904, is the home of VFW Post 76. The post was established in 1917 by twenty veterans of the Spanish-American War. The home was donated in 1946 to the post by Van A. Petty in honor of the area’s veterans of foreign wars.

The VFW Veterans Walk of Honor was created recently as part of the San Antonio River Foundation’s River Improvement Project. The beautifully-landscaped Walk of Honor will connect the historic old structure to the famed River Walk near Downtown San Antonio.

S.V. Ortega served honorably as a member of the U.S. Army Constabulary from 1945 to 1947.

<< Home